Nei giorni scorsi, abbiamo avuto il privilegio di poter intervistare, via Skype, Shane Ivey, uno degli autori del gioco di ruolo "carta e penna" Delta Green (di cui potete leggere la nostra recensione), direttamente dallo stato dell'Alabama. Durante l'intervista, sono stati molti i temi trattati, da Lovecraft all'ambientazione e alle meccaniche di Delta Green, dal game design a un'approfondita analisi dell'industria del gioco di ruolo e altro ancora.

Riportiamo, in fondo all'intervista, la stessa in lingua inglese.

L'intervista a Shane Ivey

Ciao Shane, grazie per il tuo tempo. Sappiamo che sei cofondatore e presidente di Arc Dream Publishing e autore di molti giochi di ruolo pubblicati da Arc Dream Publishing. Raccontaci qualcosa in più su di te: quando ti sei avvicinato al mondo dei giochi di ruolo? Cosa ti ha spinto a diventare un game designer e avviare la tua casa editrice?

Ciao Davide, è un piacere. Dunque, mi sono appassionato di giochi di ruolo da bambino, a dieci anni, con la prima versione del Basic di D&D ed è stato un hobby per molto tempo. Ho iniziato a farmi coinvolgere dal lato editoriale della cosa solo quando ero, oh non saprei, ero alla facoltà di giurisprudenza a New York ed essendo molto annoiato ho iniziato a testare parecchio materiale per Pagan Publishing, una società che ha prodotto manuali per Il Richiamo di Cthulhu che ho adorato e ho iniziato a lavorare con loro sempre di più per diversi anni, come volontario e come fan.

Nel frattempo, ho cambiato carriera e ho iniziato a lavorare come scrittore e come editor in altri media: su riviste, giornali, siti Web. Intanto, continuavo a lavorare come libero professionista per alcune società di giochi di ruolo come Pagan Publishing e una società chiamata Hobgoblin Press, che aveva iniziato a pubblicare un gioco chiamato Godlike, che i miei amici della Pagan avevano messo insieme.

Quindi, dopo un anno di lavoro con Hobgoblin con poca libertà di manovra, mi sono riunito con Dennis Detwiller, che conoscevo dai tempi della Pagan Publishing e che era stato colui che aveva suggerito di assumermi, e ci siamo presi una settimana per concludere un accordo con Hobgoblin per pubblicare noi stessi Godlike, attraverso una nuova società. È così che abbiamo dato il via ad Arc Dream Publishing.

È stato più o meno nel 2002, quindi è passato tanto tempo. Dopodiché ho gestito Arc Dream Publishing praticamente a tempo pieno da allora. Ma ovviamente, all’inizio sono stato solo in grado di ritagliarmi un salario a tempo pieno per un lavoro davvero a tempo pieno, sai cosa intendo, alcuni anni qua e là e così via. È così che è successo.

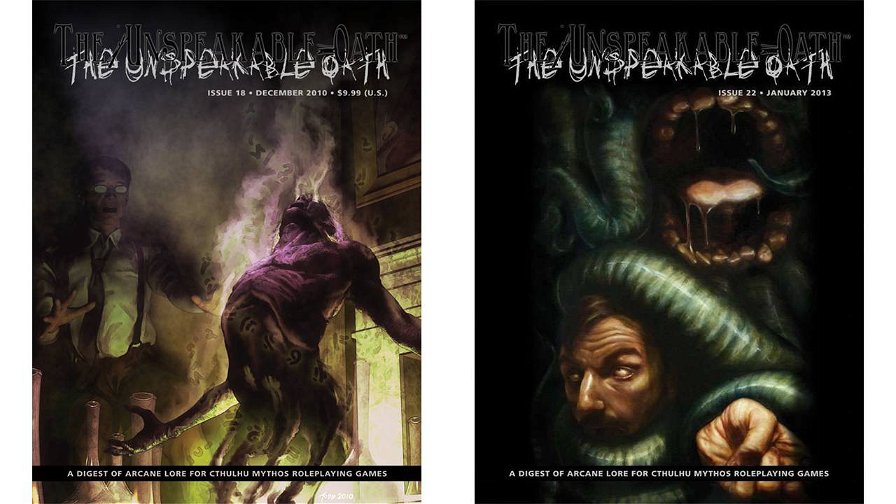

Quindi, fin da subito, abbiamo realizzato molti progetti per Godlike, per un paio di giochi spin-off basati su Godlike, come Wild Talents, una specie di grintoso gioco di supereroi, e Better Angels. E abbiamo rilanciato The Unspeakable Oath, che era la rivista di punta della Pagan Publishing, che adoravo.

E alla fine, dopo circa 10 anni, abbiamo lavorato con Pagan Publishing per iniziare a pubblicare nuovo materiale per Delta Green, che è la mia preferita tra le loro proprietà intellettuali.

E da allora questo è diventato il nostro obiettivo, poiché Delta Green, tra tutte le opere che abbiamo fatto, è quella che ha maggiore risonanza tra i giocatori. Siamo stati abbastanza fortunati ad averlo potuto realizzare, sull’onda del successo che Pagan ha avuto con esso nel corso degli anni, e di aver potuto mantenere il coinvolgimento dei principali autori di quel tempo.

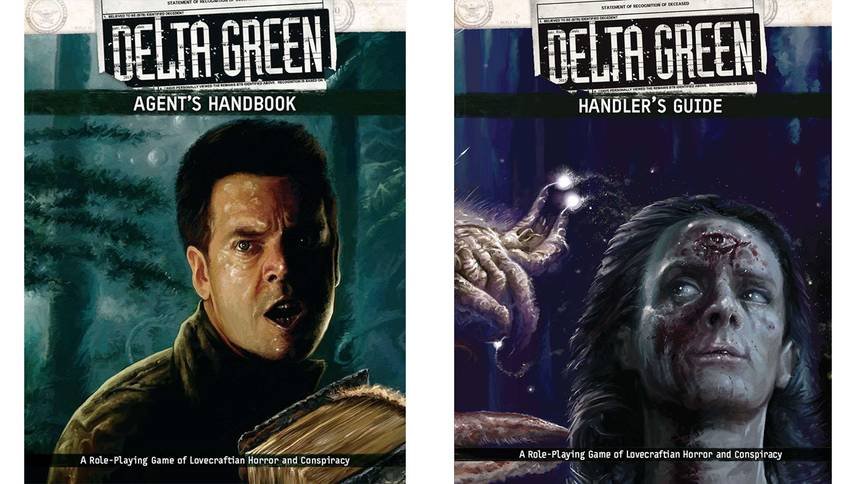

Abbiamo appena pubblicato una recensione piuttosto esaustiva dei due Manuali Base di Delta Green, ma riteniamo sarebbe stupido non approfittare della presenza di uno dei suoi autori, quindi, cos’è Delta Green?

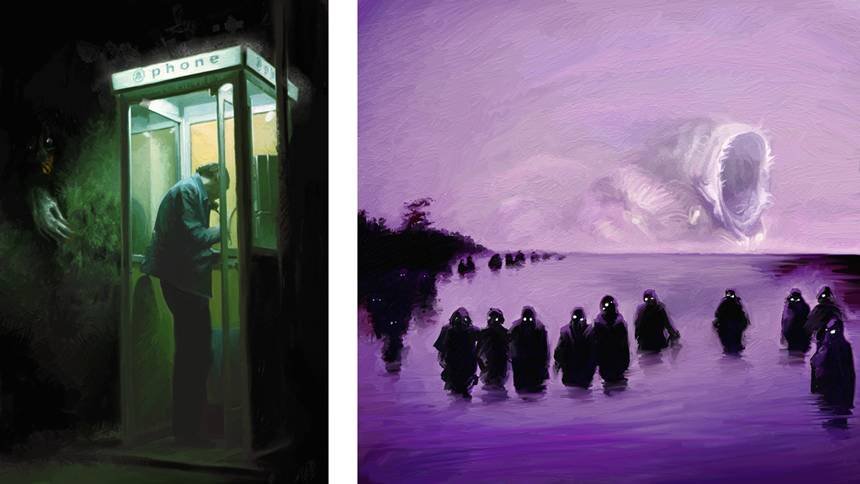

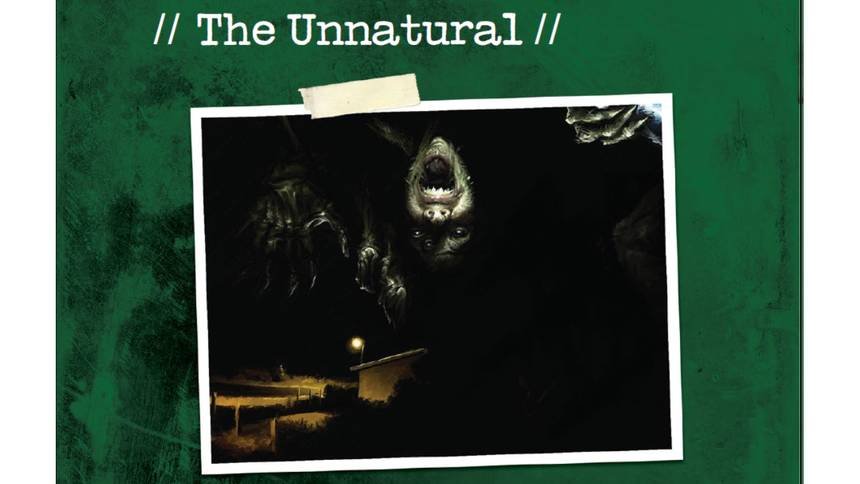

Oh sì, certo, dunque, Delta Green è un gioco di ruolo horror, è ambientato ai giorni nostri e vede i giocatori assumere il ruolo di investigatori professionisti. In altre parole, possono essere agenti di polizia o dell'FBI e così via, o possono essere anche solo medici, sai, o professori di storia o altro. Questi personaggi sono coinvolti in un'organizzazione che è consapevole dell’esistenza nel mondo di pericoli terribili, innaturali e terrificanti e si sforza di proteggerlo da questi pericoli.

E parte di questa protezione, nella mente dell'organizzazione, consiste nel tenerli segreti e nascosti, in modo da danneggiare il minor numero di persone. E così nel gioco, ai personaggi dei giocatori viene detto che c'è questa pericolosa incursione in questo posto, in questa città: "Quindi andateci e scoprite cosa sta succedendo e impedite che faccia del male a qualcun altro. E soprattutto, tenetelo segreto e tenete segreti anche noi (l’organizzazione, ndr) e cercate di non farvi ammazzare o di non impazzire nel frattempo".

Credo che la ragione per cui funzioni così bene, è perché non è così semplice come un classico gioco “entra e combatti il mostro”, ma ha tutti questi strati di segretezza e pericolo che si influenzano a vicenda come in una ragnatela. E così, i giocatori hanno costantemente qualche fonte di tensione, suspense e pericolo che colpisce i loro personaggi, indipendentemente da ciò che fanno o da quanto successo abbiano avuto.

È pensato per essere molto teso, ricco di suspense e molto emozionante e, allo stesso tempo, è pensato per evocare realmente quel senso di terrore cosmico che ti fa andare fuori di testa se ci rifletti nel modo giusto, che ci diverte così tanto.

Nella mia recensione ho scritto che se Lovecraft e Tom Clancy avessero mai prodotto un romanzo a quattro mani, il risultato sarebbe stato qualcosa di molto simile a una storia di Delta Green. Ritieni che sia sbagliato o che ci sia qualcosa di vero, in questa affermazione?

Sì, è abbastanza buona, è abbastanza buona. Abbiamo letto davvero molta narrativa thriller moderna e molto anche di storia, sai. Penso che sia un po' più vicino a John le Carré che a Tom Clancy, perché le Carré enfatizzava il tradecraft (all'interno della comunità dell'intelligence, con questo termine ci si riferisce alle tecniche, ai metodi e alle tecnologie utilizzate nello spionaggio moderno, ndr), la segretezza e i pericoli di una sorta di disonestà burocratica, il pericolo e la disumanità intrinseca nel nascondere segreti mortali alle persone, senza pensare a nulla se non alla necessità di mantenere i segreti.

Quindi, personalmente penso che Le Carré sia un paragone migliore di Tom Clancy, ma se stai cercando di far capire il punto alla maggior parte delle persone, che non conoscono la differenza tra John le Carré e Tom Clancy, certo, sì, è un'affermazione che funziona.

Negli ultimi anni, abbiamo assistito a una vera e propria esplosione di prodotti legati ai Miti di Lovecraft, tra giochi di ruolo, boardgames, librogame, merchandise e così via… Quale pensi sia il motivo di tanto successo?

Oh sì, beh, non la vedo nemmeno come una cosa necessariamente recente, certamente negli ultimi anni è esplosa perché Chaosium è tornata alla ribalta alla grande e ha pubblicato una nuova edizione de Il Richiamo di Cthulhu e ha pubblicato una linea continua e ininterrotta di manuali davvero buoni per questo brand, che ha ricevuto molta attenzione.

Ma per una decina di anni, prima di ciò, ci sono state forse una mezza dozzina di altre compagnie che hanno pubblicato su licenza libri fantastici lungo tutto il periodo: Cubicle Seven, noi ovviamente, Pagan, Golden Goblin Press e Miskatonic University.

Quindi, ha avuto successo per anni, anni e anni, se guardiamo indietro fino agli inizi, e non è mai andato via. La ragione di ciò, penso sia perché… Beh, sai, penso che ci siano molti giocatori che una volta scoperti i giochi di ruolo, si divertono un mondo - la maggior parte delle persone entra nel mondo dei giochi di ruolo principalmente attraverso giochi di avventura come Dungeons and Dragons - ma poi imparano che ci sono altri generi disponibili che offrono sensazioni diverse, giusto?

E proprio come ci sono molte persone che preferiscono vedere un film horror, un film horror surreale come White House o Annihilation, rispetto a Fast and Furious, ci sono molti giocatori che una volta provato un gioco horror e scoperto in questo genere la suspense, i pericoli per i propri personaggi e i diversi modi con cui si deve interpretare un personaggio, rispondono davvero bene a tutto ciò e questo genere di giochi diventa qualcosa in cui scaveranno e continueranno a tornare.

Personalmente, sono da sempre interessato alla capacità dei giochi di ruolo di esplorare diversi generi, poiché principalmente è ancora, per grande maggioranza, un media basato su azione e avventura, giusto? Interpreti eroi con spade o incantesimi che fanno esplodere i mostri, vai in giro e combatti, combatti, combatti e poi ottieni oro e oggetti magici che ti rendono migliore nel combattere, combattere e combattere, giusto?

Ed è fantastico, è divertente, ma è sempre interessante per me l’esistenza di un così vasto mondo di narrazioni là fuori e che ci siano così tanti modi di evocare tensione e suspense, oltre alla violenza e alle scene di combattimento. Fino ad oggi abbiamo appena graffiato la superficie delle potenzialità dei giochi di ruolo.

Ma penso, tornando alla tua domanda, che la ragione per cui le persone rispondano così bene ai giochi horror sia esattamente questa: una volta che si sono rese conto che possono ancora giocare a un gioco in cui entrano nella testa del personaggio e indirettamente vivono esperienze fantastiche, ma con un personaggio che ha sempre paura, sai, provano lo stesso tipo di brivido e quella scarica di adrenalina, che però è molto più intensa, perché stanno interpretando un personaggio vulnerabile in modi che gli eroi non sono .

E penso che questa sensazione non se ne vada mai via e che sia per questo che le persone continuano a tornare a giochi come Cthulhu e Delta Green ancora e ancora.

Delta Green è nato come un’ambientazione spin-off di Pagan Publishing per la 5a edizione di Call of Cthulhu e ha avuto una pubblicazione discontinua fino al 2010. Cosa ha spinto Arc Dream Publishing a puntare nuovamente su questa IP?

Sì, Pagan Publishing ha originariamente pubblicato Delta Green sulla rivista The Unspeakable Oath e in un grande manuale di espansione per Il Richiamo di Cthulhu del 1997, chiamato appunto Delta Green.

Sono diventato un patito di Delta Green fin da quell'articolo su The Unspeakable Oath e poi ho trascorso quattro anni, sai, aspettando disperatamente che il grande vero manuale uscisse… E si è rivelato magnifico. Quindi, pubblicarono un altro manuale più grande intitolato Countdown e poi pubblicarono una manciata di prodotti più brevi, che non venivano venduti attraverso i negozi, così che non dovettero infrangere le loro limitazioni dovute alla licenza legata a Il Richiamo di Cthulhu.

Ma in quel periodo, John Tynes, ora John Scott Tynes, che era il responsabile della Pagan Publishing, organizzando e gestendo tutto, passò al mondo dei videogiochi e così la produzione di Pagan Publishing si interruppe bruscamente, era circa il 2000, 2001. Come ho detto, io iniziai circa un anno o due più tardi, e Dennis e io iniziammo a lavorare insieme a stretto contatto e così, sin dall'inizio, lui e io abbiamo parlato in privato di come avremmo potuto far ripartire Delta Green e tornare a scriverne.

Io avevo molte idee per questo progetto e lui, che era uno dei creatori, era ugualmente pieno di idee che voleva vedere prendere forma. Ci sono voluti solo pochi anni per ingranare abbastanza bene come azienda e sistemare le cose con Pagan Publishing, che ora è gestita da Scott Glancy, uno degli altri creatori di Delta Green.

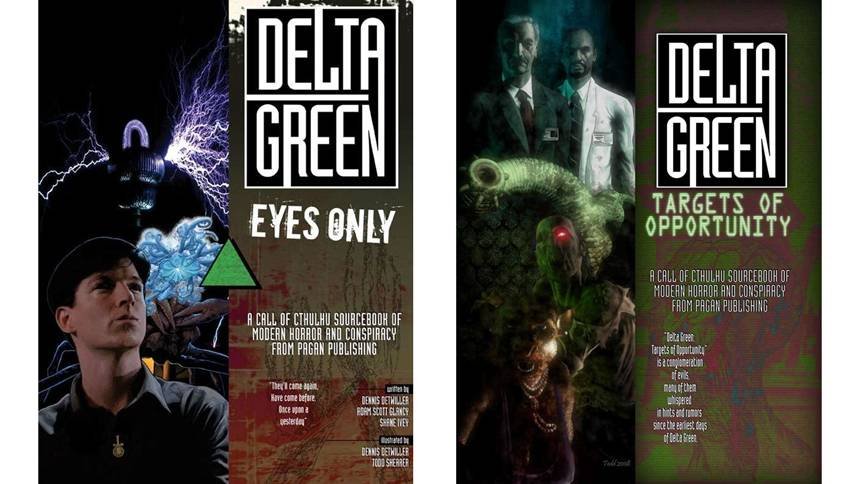

E per iniziare, come Arc Dream abbiamo pubblicato due manuali Delta Green, uno chiamato Eyes Only e uno intitolato Targets of Opportunity. Beh, in realtà sono stati pubblicati ufficialmente da Pagan Publishing, Arc Dream li ha creati e venduti a loro. Sai, li abbiamo creati come studio, li abbiamo realizzati, li abbiamo impacchettati e li abbiamo pubblicati attraverso Pagan Publishing, proseguendo lentamente e in collaborazione con Scott Glancy. Quindi, lo hanno pubblicato loro sotto la licenza che avevano con Chaosium.

In pratica, c’è stata essenzialmente un’interruzione in Delta Green dal momento in cui è uscito Countdown nel 2000 fino al 2007, quando è uscito Eyes Only. E per tutto quel tempo, abbiamo discusso su come avremmo potuto riportarlo in auge. È stato verso il 2004 che abbiamo iniziato davvero a lavorare sodo per mettere insieme Eyes Only. Ci sono voluti solo un paio d'anni per realizzarlo.

Trovare un modo per far funzionare Delta Green è sempre stato parte del nostro obiettivo. Dennis e io, oltre ad adorare questa proprietà intellettuale e amare lavorare su di essa, sapevamo che il pubblico era ancora tutto lì, poiché abbiamo continuato a interagire con i fan ogni giorno, attraverso mailing list e siti Web. E gli appassionati sono rimasti altrettanto attivi durante il periodo in cui non è uscito materiale, come quando i manuali uscivano con frequenza.

Quindi, una volta sistemato tutto, abbiamo lanciato Target of Opportunity nel 2010 e ha funzionato bene. Di conseguenza, abbiamo immediatamente iniziato a concentrarsi su come lanciare Delta Green come un gioco a sé stante. Non abbiamo mai avuto in mente di fare un reboot del prodotto, perché fin dall'inizio era nostro esplicito desiderio che chiunque avesse acquistato in passato del materiale per Delta Green, potesse usare quei manuali e quelle regole con qualunque cosa fosse uscita in seguito.

Non volevamo rendere nulla obsoleto, ma abbiamo trascorso molto tempo nel corso di diversi anni a capirlo, lavorando e parlando tra di noi. Abbiamo coinvolto alcuni nostri colleghi straordinariamente esperti nei Miti di Cthulhu, sia come mitologia sia come proprietà intellettuale, così da poter stabilire i confini di ciò che avremmo potuto fare con questa proprietà, che non entrasse in conflitto con quanto prodotto dai nostri amici in Chaosium.

Poiché non volevamo pestar loro i piedi, ma non volevamo nemmeno essere limitati da una licenza che ci richiedesse di ottenere l'autorizzazione di qualcun altro ogni volta che volevamo produrre qualcosa. E nel frattempo, i nostri amici della Pelgrane Press avevano creato Trail of Cthulhu, che ha adottato approcci ancora diversi; quindi, in questo ambito erano successe molte cose, che hanno suscitato il nostro interesse e generato idee.

Dopo aver pubblicato Targets of Opportunity, ci sono voluti solo pochi anni per capire tutto ciò e decidere come volevamo che fosse il nuovo regolamento e quali sensazioni dovesse suscitare. Ci è voluto davvero molto lavoro prima che sentissimo di poter dire ufficialmente: "ecco cosa stiamo facendo" e presentarlo ai fan, sai, per raccogliere fondi per realizzarlo.

Quali sono state le maggiori sfide che hai dovuto affrontare nello sviluppo di Delta Green?

Oh, beh, penso che la sfida più grande sia sempre ottenere l'atmosfera e il tono giusti, poiché con Delta Green il nostro approccio è diverso dal modo in cui sono scritti la maggior parte dei manuali di Cthulhu, è diverso dal modo in cui vengono presentate la maggior parte delle avventure dei Miti di Cthulhu. Dennis e io in particolare, e John Tynes e Scott Glancy, abbiamo tutti una sorta di intuito istintivo di come dovrebbero essere, sia nella percezione sia in gioco, ma esprimere tutto ciò è molto più difficile.

E anche produrre manuali e avventure che abbiano quella sensibilità, è sempre una specie di sfida. Poiché anche come autori, per ognuno di noi è molto facile concentrarsi sui dettagli del mondo, i dettagli storici, i dettagli procedurali su come funzionano queste cospirazioni e organizzazioni segrete, per poi perdere la concentrazione sul tono e sulle sensazioni che tutte le cose soprannaturali dovrebbero evocare.

Penso che ogni volta sia questa la più grande sfida, soprattutto perché, sai, come dico sempre, anche quelli di noi che sono autori con la più profonda esperienza con questo scoglio, ancora ci inciampano sopra e dobbiamo sempre lavorare l'uno con l'altro, per essere sicuri di sapere tutto.

Ogni volta che scrivo qualcosa per Delta Green, lo invio al resto del gruppo dei partner, Dennis Detwiller, Scott Glancy e John Scott Tynes, in modo che possano leggerlo, rivederlo e segnalare: "Ok, questo non sembra giusto, questo non sembra giusto, questa parte qui è fantastica ...", capisci, e lo facciamo tutti l'uno con l'altro. Quindi, ogni volta che Dennis scrive qualcosa, lo passo al setaccio e gli invio milioni di note fastidiose.

Ma questo fa parte del processo ed è così che ci assicuriamo che tutto ciò che facciamo sia buono, poiché nessuno di noi mette in campo il proprio ego. Nessuno di noi fa il prezioso, siamo tutti qui per servire la proprietà intellettuale, poiché il suo valore è qualcosa che condividiamo insieme. Quindi sì, penso che questa sia la sfida più grande, assicurarsi che ogni cosa di Delta Green, non importa quale sia il soggetto, abbia quella sensibilità cupa e desolante.

Perché sappiamo che i giocatori porteranno al tavolo di gioco il loro senso dell'umorismo, porteranno il loro tipo di commedia nera, i loro scherzi di cattivo gusto e altri modi per far fronte al duro senso cosmico, quasi nichilista, del mondo che stiamo dando loro. Dunque, vogliamo deliberatamente tenerlo il più oscuro possibile, per così dire. Sì, questa è la sfida più grande, ci sono molte altre sfide, ma questa è la più grande.

Le regole di Delta Green mantengono alla propria base il sistema Basic RPG di Chaosium, ma introducono moltissime novità e un game design che ho davvero molto apprezzato, dal lethality rating alla gestione della sanità mentale. Una meccanica che definirei fondamentale è quella dei Bonds e di come il contatto con l’innaturale vada a erodere le vite dei personaggi, assieme all’assunzione di alcol e droghe per poter tirare avanti, nonostante ciò cui si è stati testimoni. Tutto questo rende Delta Green un prodotto molto adulto, feroce e cupo. Dicci qualcosa a riguardo, come siete arrivati a queste fantastiche regole?

Grazie! Ritengo che ognuna di queste novità introdotte sia interessante, poiché ognuno di quegli elementi del regolamento, è nato indipendentemente dagli altri e in momenti diversi e, in alcuni casi, da autori diversi. Le regole sulla lethality, ad esempio, sono state sviluppate da Greg Stolze, con cui abbiamo lavorato su Delta Green: the roleplaying game.

Greg è stato lo sviluppatore dei regolamenti di Godlike,Wild Talents, Better angels, tutti fantastici giochi, e Unknown Army, che adoriamo, come adoriamo lavorare con lui. Questo è un aneddoto divertente, ricordo quando ci ha raccontato dell'esperienza che lo ha ispirato a inventare quella regola.

È stato durante una partita a cui ho giocato insieme lui un anno alla Gen Con, Scott Glancy stava masterizzando; non era una sessione di Delta Green, era un gioco sulla Prima Guerra Mondiale e stavamo interpretando dei marinai in un sottomarino. E il sottomarino incontra qualche orribile, diabolico, mostruoso culto da qualche parte, e a un certo punto uno dei giocatori impazzisce. Era a una mitragliatrice sul sottomarino e dice: "Inizierò a uccidere tutti" e così Scott: "Okay, tira per i tuoi attacchi con la mitragliatrice".

E in quel momento, l'intero gioco si è fermato. Quel giocatore ha iniziato a lanciare i dadi: “Ok, ecco un tiro per colpire, ecco un tiro per colpire, ecco un tiro per colpire, ecco quanti proiettili si prende questo tizio, ora tiriamo i danni per ognuno di questi proiettili ...”.

E Greg ci ha detto che è stata quella l'esperienza, quello è stato il momento in cui si è chiesto se ci potesse essere un modo migliore per gestire la cosa. E così ha iniziato, ha giocato con quell'idea qua e là per un paio d'anni e poi, quando stavamo mettendo insieme il gioco di ruolo di Delta Green, ci ha inviato l’idea. Probabilmente, il gioco era già finito all'85-90% circa e pronto per essere pubblicato a quel punto.

Abbiamo fatto molti playtest e abbiamo semplificato un paio di elementi qua e là e quindi tutto era pronto. È stato brillante da parte sua, ha visto una sfida, e ha compreso che l'aggiunta di una nuova regola poteva aumentare sia il divertimento del gioco sia la suspense e il senso di paura nei giocatori allo stesso tempo.

È stato un genio, adoro il modo in cui queste regole funzionano quando entrano in gioco. Le altre cose, le modifiche che abbiamo apportato alle regole sulla sanità mentale e sui bonds, sono state principalmente un mio lavoro. Mi sono avvicinato a quegli elementi fondamentalmente perché c'erano parti delle regole esistenti sulla sanità mentale che io amavo davvero, ovviamente, o non avrei mai giocato a questi giochi per, sai, 20 o 30 anni, ma sapevo anche che le dovevamo ambientare ai giorni nostri.

Stavamo ambientando Delta Green nel mondo reale, e molti dei giocatori hanno avuto davvero recenti esperienze di guerra e traumi; e proprio quei traumi che stavamo replicando nel gioco, trasformandoli in un elemento di divertimento. E quindi, volevo davvero assicurarmi che il corso delle esperienze di un agente Delta Green nella fiction sembrasse familiare a qualcuno che avesse conoscenza ed esperienza diretta di com’è affrontare certi terribili traumi nel mondo reale.

E una parte chiave di tutto ciò è l'impatto che il PTSD (disturbo post traumatico da stress, ndr) e gli altri sintomi e sindromi da trauma hanno, non solo sull'individuo che ne soffre, sul paziente, ma su tutti coloro che lo circondano, tutta la sua famiglia, tutti i suoi amici e che, nella mia esperienza, non è mai stata una caratteristica dei giochi horror. È qualcosa che si è stati in qualche modo incoraggiati a conoscere come giocatori e mai affrontata nei regolamenti.

Quindi, ho pensato che sarebbe stato molto più interessante e potente avere alcune parti di tutto ciò da incorporare nelle regole che avremmo presentato ai giocatori. E una volta che ho iniziato a lavorarci, ho studiato molti testi di psicologia e sui traumi, e ho condotto interviste con psicologi che lavorano con il Veteran Affairs Bureau, qui negli Stati Uniti, che lavora con i soldati, i nostri veterani, per far fronte alle dipendenze e al PTSD.

Affinché potessimo sperimentare l'esperienza di ciò che accade nel gioco, era importante che sembrasse reale e che ci avvicinassimo con serietà, che fosse chiaro che non stavamo cercando di buttare tutto sullo scherzo; è stata quindi un grande sfida. È stato un processo davvero soddisfacente per me, perché è un piccolo insieme di regole che per metterlo su carta ho dovuto passare, senza rendermene conto, vent'anni a prepararmi, ma che sapevo istintivamente che avrebbe avuto un ruolo importante nel nuovo gioco e che sarebbe stato un elemento distintivo da qualsiasi altra cosa che avessimo fatto in precedenza.

Quindi, è così che è nato. Poi ci sono altre modifiche al motore di gioco, ma la maggior parte sono abbastanza minori e vanno ad agire in alcune meccaniche molto dettagliate. Come sai, è un motore basato sulla percentuale e sul lancio di dadi percentuali: se il tiro è sufficientemente basso, allora hai successo. Ma poi entra in gioco la possibilità che si possa avere un successo davvero, davvero, buono, che in alcuni giochi si traduce nell'aver tirato una certa frazione del punteggio di riferimento: se si ha una probabilità del 50%, se si tira entro la metà, allora si è fatto meglio, se si tira un quinto, allora si è fatto meglio e così via…

Quindi, ho parlato con Greg Stolze e abbiamo preso in prestito alcune idee che aveva messo in pratica in Unknown Armies e che avevamo visto anche in altri giochi, come Pendragon ed Eclipse Phase, per trovare un'alternativa a quanto detto prima, per realizzare un sistema molto più facile e più intuitivo.

Quindi, invece di avere utilizzato il sistema basato sulle frazioni dei punteggi, in Delta Green si continua a tiare i dadi percentuali per ottenere un risultato più basso del valore di riferimento, ma per avere un risultato eccezionale si guarda se i numeri usciti sono doppi (11, 22, 33, 44 e così via, ndr). E questo ha risolto immediatamente tutti i problemi.

Questa è un esempio molto specifico, e siamo intervenuti in modo simile con molte parti del motore di gioco, per snellire e semplificare il gioco.

Ho particolarmente apprezzato anche la scelta di dare al gioco un punto di vista più scientifico e meno “magico” dei Miti di Cthulhu. Abbiamo a che fare con ipergeometria e ipermatematica più che con forze magiche ed esoteriche. Anche la scelta della parola “innaturale” al posto del più comune “soprannaturale” è un chiaro segnale di questa scelta stilistica, che ritengo sia più in linea con la poetica di Lovecraft. Cosa vi ha spinto a decidere in tal senso? Credete possa aver spiazzato alcuni giocatori l’allontanarsi dalla comfort-zone della magia cui sono abituati da anni?

Oh sì, penso che abbia funzionato bene per i giocatori, non credo di aver sentito nessun giocatore che abbia letto i manuali a cui non sia piaciuto questo approccio. E come dici tu, quella è stata una scelta deliberata e molto ponderata che abbiamo fatto e che volevamo rafforzare in tutto il regolamento, in particolare nella Handler’s Guide. Abbiamo scritto tutto ciò partendo dall'idea che il giocatore stia leggendo nei panni di un agente Delta Green e quindi, tutte le informazioni che ha arrivano attraverso il filtro di questa cospirazione segreta.

E l'organizzazione segreta applica tutte queste precise etichette scientifiche a cose che non capisce, proprio perché non le capisce. Quindi, dare alle cose un suono molto scientifico, un'etichetta molto scientifica, dà loro l'illusione di avere una sensazione di comprensione o controllo su di esse. Un controllo che in realtà non ha.

Così, usiamo la terminologia per evocare tutto ciò e allo stesso tempo anche per continuare a ricordare ai giocatori, sottilmente o in modo subliminale, che i loro personaggi e le persone di cui si fidano non sanno davvero cosa stanno facendo e che quindi il terreno sotto i piedi è decisamente instabile.

E allo stesso tempo, ciò che hai detto, sembrava adatto al modo in cui Lovecraft scriveva. Come abbiamo detto molte, molte volte, bisogna ricordare alle persone che le storie di H.P. Lovecraft spesso appaiono molto pittoresche e molto arcaiche perché stiamo leggendo oggi racconti che furono scritti negli anni '20 e '30 e che non è così come ci appaiono oggi che l’autore le intendeva. Stava scrivendo di scienza all'avanguardia, stava componendo tutte le sue migliori storie basandole sulla comprensione scientifica più avanzata nel momento in cui scriveva.

Prendiamo il racconto Il Richiamo di Cthulhu, per esempio. Come sai, gran parte dell'impulso della storia derivava da ciò che stava imparando sulla radio e su come funzionino le onde radio. Ovviamente, trovava tutto ciò affascinante e un po’ strano. E così si è informato sul senso di queste onde invisibili e questi schemi di energia di cui non abbiamo idea che siano là fuori, ma che quando sintonizziamo insieme un paio di aggeggi, allora magicamente iniziano a essere decifrati in qualcosa che possiamo capire.

Voglio dire, se lo guardi dal suo punto di vista, è una cosa molto, molto inquietante, se ci pensi. Ritengo che provenga da qui la suggestione per la storia Il Richiamo di Cthulhu. In combinazione con il suo fascino per la mitologia, per l'epoca della mitologia e delle storie, per tutto ciò che paleontologi, geologi e astronomi in quel periodo stavano cercando di capire: come la Terra, le stelle e le galassie si erano formate.

Tutte queste cose, nel periodo in cui scriveva, erano assolutamente scienza all'avanguardia. E così, con Delta Green vogliamo portare ulteriormente avanti questa tematica e fare del nostro meglio per presentare e ricreare quella specie di vertigine data dalla comprensione cosmica di cose che solo ora l’uomo sta iniziando a scoprire.

Ovviamente, tutti conosciamo perfettamente la radio, quindi non ci preoccuperemo di questo, ma sai, c'è l’ingegneria genetica, ci sono ancora cose da scoprire sul processo evolutivo, ci sono ancora cose da scoprire sull'astronomia, sulla formazione dell'universo. Non sappiamo ancora se la materia oscura esista davvero.

E in un certo senso, se inizi a pensare a tutte queste cose da una prospettiva diversa, come Lovecraft ha fatto con la radio, tutte possono evocare cose molto, molto, strane e inquietanti, che sembrano istintivamente pericolose e minacciose per il posto che l'umanità ha nell'universo. Questo è esattamente il nostro approccio a tutto ciò e sebbene nessuno di noi sia uno scienziato, conosciamo molti scienziati e facciamo del nostro meglio.

Nei manuali vi è solo un brevissimo accenno relativo alle Dreamlands e nessun riferimento alle creature a essa associate, come i magri notturni, i ghast e così via… È prevista un’espansione dedicata a questi argomenti?

Sì, un giorno metteremo insieme un manuale sulle Dreamlands, non so ancora quando. Abbiamo molte idee su questo argomento, ma il motivo per cui non l'abbiamo affrontato nell’Handler’s Guide è perché le “lenti dei sogni” sono un argomento molto ampio. Anche il tono delle storie che Lovecraft ha scritto e da cui avremmo tratto spunto, specialmente La ricerca onirica dello sconosciuto Kadath, è così diverso da quello delle storie dei Miti di Cthulhu a cui ci ispariamo, che se avessimo affrontato l’argomento, sarebbe sembrato che avessimo inserito nell’Handler’s Guide qualche pagina realizzata per un gioco completamente diverso.

Sarebbe sembrato fuori posto e distraente. Ci sono volute un sacco di discussioni, di decisioni e ripensamenti, per arrivare a questa decisione. Ma abbiamo molte idee per questo argomento e c'è anche da tenere presente il mito di Carcosa, di cui Robert Chambers ha scritto. Potenzialmente, c'è molta sovrapposizione di temi tra Carcosa, questo strano altro mondo che ha diversi livelli di tecnologia e dove le cose sono un po' oniriche, e le Dreamlands, in cui abbiamo un altro strano mondo con diverse tecnologie e mostri e in cui le cose sono un po’ oniriche.

Ma il mito di Carcosa è molto legato alla storia di Delta Green, sapevamo che doveva essere presente e ciò significava che era maggiormente necessario lasciare le Dreamlands da sole, così da non confondere le persone. In questo modo potremo affrontarle più avanti, in modo più completo e che risulti più interessante e spaventoso per i giocatori.

Possiamo quindi aspettarci un manuale sulle Dreamlands e uno sul Re in Giallo e Carcosa?

Sì, beh, il prossimo libro che pubblicheremo sarà Impossible Landscapes, una lunga campagna autonoma di avventure che hanno a che fare con il Re in Giallo e Carcosa e che si addentrerà in quella mitologia con grande, grande, grande profondità. È in lavorazione ora, stiamo per inviarlo alla fase di editing finale, quindi lo invieremo al layout, in modo da poterlo stampare in pochi mesi.

È fantastico, è un lavoro di Dennis Detwiller e John Scott Tynes. Dennis ha lavorato a stretto contatto con John fin dagli inizi nello sviluppo dell'approccio di Delta Green al Re in Giallo e nel ruolo che questa mitologia ha avuto nell'ambientazione. Questo è uno di quei progetti su cui ha passato quasi trent'anni a riflettere e infine, negli ultimi due anni, ha iniziato a metterlo su carta.

Continuando a parlare dell’ambientazione, in questa nuova edizione di Delta Green, le cospirazioni presenti nella precedente edizione, come Majestic 12, la Karotechia, The Fate e così via, sono state praticamente spazzate via, lasciando comunque qualche strascico. Come mai questa decisione? Erano un nemico troppo anni ’90? Ci saranno nuove cospirazioni da affrontare?

In parte è ciò che hai detto, per cui abbiamo adottato questo approccio in cui, invece di avere quattro o cinque organizzazioni molto ben sviluppate a cui opporsi, abbiamo deciso di fare un salto in avanti, lasciando tutto nel passato della linea temporale, raccontando e dando per assodato che Delta Green abbia già affrontato e sistemato tutto in qualche modo.

In gran parte perché volevamo in qualche modo avere una lavagna pulita, per così dire, su cui lavorare e anche perché, onestamente, quelle idee erano già in circolazione da vent’anni. Quindi, se qualcuno vuole giocare qualcosa di veramente profondo ed elaborato, per esempio con la Karotechia, va bene, quelle idee ci sono già!

Inoltre, c'era un altro problema: il modo in cui le persone percepiscono le cospirazioni pericolose è cambiato nel corso degli anni. Negli anni '90, quando i manuali di Delta Green furono creati per la prima volta, l'idea che ci fossero queste grandi organizzazioni segrete ed elaborate, che erano pericolose e ben gestite e che costituivano una seria minaccia se si veniva scoperti a ficcanasare, ma che altrimenti non avresti mai saputo della loro esistenza, era una sensibilità molto comune negli Stati Uniti. Si adattava perfettamente a quegli anni.

Non si adattava altrettanto bene però al periodo in cui stavamo ambientando la nuova edizione. Stavamo portando avanti l’ambientazione agli anni 2010, ora agli anni 2020 ma al momento erano gli anni 2010. E a quel tempo, ovviamente, tutti nel mondo sapevano molto più di quanto volessero, a proposito di cospirazioni segrete mortali. E quindi dovevamo assicurarci che ciò di cui stavamo parlando avrebbe intuitivamente avuto senso per le persone e non volevamo sentirci come se stessimo facendo qualcosa per farle stare meglio, fingendo che queste cospirazioni mortali fossero più elaborate e più competenti di quanto fossero in realtà.

Il fatto è che non devi per forza avere una cospirazione internazionale con gli scopi della Karotechia, sai di cosa parlo, quei nazisti resuscitati che gestiscono bande in tutto il mondo per causare un’assolutamente straziante carneficina. La conoscono tutti perfettamente ora, quindi è diventato importante per noi concentrarci su cospirazioni mortali soprannaturali, cose che spesso sono venute alla luce in modo indipendente l'una dall'altra, non a causa della pianificazione, non a causa di un'organizzazione elaborata.

Ma bensì perché gli esseri umani, quando si sentono frustrati e quando vogliono più di quello che possono ottenere facilmente, cercano scorciatoie. E molti di loro cercano scorciatoie pericolose e violente. E nel mondo di Delta Green, le altezze a cui si può arrivare per fare propria un terribile potere in grado di scatenare violenza e distruzione sono molto maggiori di quanto lo siano persino nel nostro mondo.

E così, abbiamo voluto dare la sensazione che ciò che Delta Green sta affrontando non sia un'organizzazione che si può abbattere, come potrebbe essere per esempio la mafia, che ciò con cui si deve confrontare sono mille piccoli punti di orrore che continuano a emergere in continuazione. E che affrontarli potrebbe non essere mai abbastanza. E che potrebbero aumentare sempre più velocemente, perché viviamo in un mondo di onnipresente e istantanea comunicazione di idee.

E alcune di queste idee, nel mondo di Delta Green, sono tipo: "Ehi, ho escogitato un modo per evocare questo potere straordinario e sorprendente e non ci sono conseguenze!". E quando queste conseguenze invece arrivano e il malvagio mostro invisibile ti divora, hai già convinto altre persone in altre parti del mondo a provarci.

Quindi, sono state molte le ragioni per cui abbiamo adottato questo approccio, allontanandoci dalla presentazione di alcune grandi organizzazioni dettagliate e incoraggiando invece i Master a inventare le proprie incursioni su scala minore ed eventualmente collegarle tra loro in qualunque misura desiderino.

Tutto ciò lo approfondiamo con un nuovo manuale, che è disponibile ora in PDF e la cui edizione rilegata è in questo momento su un mercantile che sta attraversando il Pacifico in direzione degli Stati Uniti. Si intitola The Labyrinth, è scritto da John Scott Tynes, e tratta di quattro organizzazioni con cui Delta Green potrebbe interagire. Queste hanno accesso a pericolosi segreti innaturali, e potrebbero essere alleati o semplicemente degli innocenti astanti, e quindi in terribile pericolo a causa delle loro interazioni con Delta Green.

Inoltre, presenta anche altre quattro organizzazioni che stanno deliberatamente cercando terribili pericoli innaturali, su cui Delta Green deve indagare. Ma non si tratta di cospirazioni su larga scala che abbracciano il mondo, ognuna di esse non è altro che un nodo isolato di rancida miseria che è emerso, di cui si verrà a conoscenza e su cui si dovrà indagare.

E più in particolare, The Labyrinth, suggerisce come collegare quei gruppi ai personaggi dei giocatori e a Delta Green, e quali connessioni creare e come dovrebbero apparire le comunicazioni in gioco e come rendere queste comunicazioni un'altra fonte di orrore e terrore per i giocatori.

Un altro aspetto che ho trovato interessante è il “ritorno alla legalità” di Delta Green e la guerra fredda tra the Program e the Outlaws. Entrambe le fazioni sembrano avere sia valide argomentazioni sia zone oscure, che siano una certa propensione al compromesso o un fanatismo alla causa portato all’estremo. In Delta Green non ci sono buoni e cattivi, bianco e nero, bensì cinquanta sfumature di grigio entro cui i personaggi dovranno muoversi, mettendo in gioco la propria etica e moralità. Di certo, non è un gioco per tutti, probabilmente molti giovani giocatori non sono in grado di capire quanto sia profondo il gioco e quanto profonda debba essere giocare il ruolo.

Sì, hai assolutamente ragione, non è per tutti. Penso che sia interessante il fatto che tu abbia detto che molti giocatori più giovani potrebbero non rispondere allo stesso modo dei giocatori più esperti o più anziani. Se hai 30 o 40 o 50 anni, hai un’ottica diversa su come sia la vita, su quali siano le responsabilità, su cosa comporterà se il tuo personaggio fallisce nell’ottemperare quelle responsabilità.

Probabilmente sai in prima persona quanto sia terribile quando commetti un errore e la tua famiglia ne soffre, mentre se sei un giocatore più giovane, in molti casi è molto più difficile trasmettere tutto ciò. Allo stesso tempo, ci sono molti giovani giocatori, che abbiamo sentito online, che hanno iniziano a giocare e si divertono molto.

Non è per tutti, come dici tu, ci sono alcuni giocatori a cui non piace il focus, ci sono molti giocatori che vogliono giocare di ruolo per allontanarsi dal pensiero di tutte le responsabilità e di tutti i modi con cui il mondo può rivoltartisi contro, rivelandosi una fonte di terrore, giusto? Hanno già abbastanza stress.

Ma sappiamo che giocatori di tutti i ceti sociali apprezzano Delta Green e il nostro approccio alle cose e il modo con cui offriamo a Master e giocatori di esplorare temi molto, molto oscuri che fanno riflettere, ma in un contesto di gioco e finzione. Si può esplorare tutto ciò e anche riderci sopra, con quel tipo di umorismo nero che credo sia assolutamente cruciale nella maggior parte delle partite di Delta Green.

Per quanto mi riguarda, adoro vederlo in gioco, in una certa misura, perché dimostra che i personaggi stanno sprofondando. È una specie di riflesso, un meccanismo di difesa per elaborare cose che sono travolgenti a livello emotivo. Ed è per questo motivo che questo tipo di umorismo è così diffuso, per lo meno negli Stati Uniti, ad esempio tra gli agenti di polizia.

Intendo dire, c'è una cosa che chiamiamo "umorismo da poliziotto", perché la polizia di solito è molto attenta a non farlo in pubblico o di fronte a chiunque non sia nella loro cerchia, perché potrebbe causare dolore negli altri. Ma sai, la maggior parte dei poliziotti ha affrontato così tanta morte, così tanto sangue, violenza e comportamenti terribili, sia tra il pubblico che tra i loro simili, i loro compagni agenti, che devono avere un senso dell'umorismo su tutto ciò, come valvola di sfogo, o diventa solo una fonte di miseria che li fa impazzire.

Ci siamo accorti che i giocatori che rispondono a questa tipologia di gioco sembrano attraversare tutti i tipi di linee demografiche. Ed è sempre molto gratificante soprattutto vederlo emergere tra quelle persone di cui stiamo scrivendo nella nostra narrativa.

Abbiamo parlato con soldati veterani, con agenti dell'FBI e agenti dell'intelligence del mondo reale, che ufficiosamente ci hanno detto di amare Delta Green, adorano giocarci e amano il modo con cui ci siamo avvicinati. E allo stesso tempo, abbiamo scoperto che piace anche alla gente comune, che trova l'argomento interessante e avvincente e piace anche agli infuriati e irriducibili liberali progressisti, come la maggior parte di noi dello staff di autori.

È sempre affascinante per me parlare con i fan e avere un'idea di tutte le diverse direzioni da cui provengono e di tutte le prospettive con cui stanno giocando e di cosa stanno trovando nel gioco.

Pur avendo una discreta cerchia di appassionati, Delta Green è poco conosciuto in Italia. Cosa vuoi dire ai giocatori italiani per convincerli a provare Delta Green?

Oh sì, beh, le ragioni per giocare a Delta Green… Prima di tutto perché è un gioco horror e non è un gioco horror spaltter e con mostri, non riguarda Jason di Venerdì 13. Ha a che fare maggiormente con il senso di terrore cosmico che si avverte quando si realizza qual è lo scopo del mondo e la nostra insignificanza in esso. E quindi venire a patti con quella rivelazione e presentarla sotto forma di creature che puoi uccidere, forse, o che potrebbero mangiarti, che è più probabile.

In un certo senso introduce il sangue e la sgradevolezza di quel tipo di viscerale orrore personale nel contesto cosmico del: "Oh mio Dio! In cosa sono incappato!", rendendolo nuovamente personale nella realizzazione, poiché ha a che fare con le conseguenze di affrontare tutto ciò.

E quindi, conduci queste indagini mortali, ma devi mantenere tutto quanto il più segreto possibile. E se non dovessi riuscire a mantenerlo mortalmente segreto, ciò comporterà terribili guai per te, per la tua carriera, la tua famiglia e tutti quelli che ti stanno intorno. Quindi, quando giochi c'è sempre questo senso di suspense proveniente da ogni singola direzione.

E il gioco va via liscio, abbiamo deliberatamente reso le regole facili da gestire. Volevamo che queste e i dadi fornissero tutte le idee e il senso di suspense di cui si ha bisogno, senza che si debba smettere di pensare al proprio personaggio per iniziare invece a preoccuparsi delle regole.

Non so quale sia il tipo di prodotto di successo dei grandi media nel genere horror o nella suspense in Italia, ma negli Stati Uniti direi semplicemente: “Se ti piacciono gli X-Files, ma vorresti che fosse più oscuro e vorresti che Scully e Mulder non fossero così tanto protetti dalla sceneggiatura, questo è un buon quadro di riferimento per Delta Green. Se ti è piaciuta la prima stagione di True Detective...”.

Sai, True Detective ha preso in prestito molte cose da Delta Green, così come ha preso molte cose da molti altri autori, e ciò significa che se prendi ciò che accade in quella serie, se lo guardi e poi aggiungi uno strato di "Oh, e ci sono anche orrori davvero innaturali che stanno per emergere nel frattempo", questo è un altro buon quadro di riferimento. Se vuoi quel senso di terrore e quel senso di terribili, terribili conseguenze al tavolo da gioco, Delta Green è ciò che fa per te.

Parliamo più in generale del settore dei giochi di ruolo. Data la tua esperienza nello sviluppo di giochi di ruolo, come è cambiato l'approccio al game design dei giochi nel corso degli ultimi decenni?

Bene, non ne sono davvero sicuro, non so se il processo di progettazione sia cambiato molto nel tempo, se non come le persone rispondano ai cambiamenti. Voglio dire, nel mondo dei giochi di ruolo non si scappa, è Dungeons & Dragons la proprietà intellettuale che definisce il genere e quindi di riflesso definisce il settore.

Tutto ciò che gli altri fanno è, che lo vogliano o meno, una reazione, una risposta a ciò che Dungeons & Dragons sta facendo. Allo stesso tempo, negli anni Dungeons & Dragons ha imparato da ciò che hanno fatto tutti gli altri.

La quinta edizione di Dungeons & Dragons, ad esempio, prende in prestito alcune idee davvero valide da piccoli giochi indipendenti, che si concentravano deliberatamente su cose come i legami tra gli avventurieri, i loro ideali, come un allineamento del personaggio, che tu sia buono o cattivo o altro, si manifesta nel suo comportamento, di modo che le persone attorno a lui lo notino... E fornivano suggerimenti per portare tutto ciò sul tavolo da gioco e meccaniche che offrivano una ricompensa per averle giocate.

Penso che il fare avanti e indietro tra i giochi e il design dei giochi sia una cosa che si è evoluta nel tempo. Ora è diventato molto istintivo, in modi che se stessimo pubblicando negli anni '90, per esempio, non sarebbero esistiti. Parte di ciò è perché c'erano molti meno giochi là fuori.

In quel periodo le persone stavano iniziando a realizzare il potenziale di questo mezzo. Quando Over the Edge uscì, era rivoluzionario, perché ti diceva esplicitamente: “non preoccuparti di tutti questi dettagli, lancia i dadi; sono pochi dadi a sei facce in base a quanto sei bravo a fare qualcosa di veramente generico. E a seconda del tiro, inventa, non deve essere specifico”. Questa è stata un'idea fondamentale, è così semplice che oggi non ci penseremmo nemmeno, ma è stato un grosso cambiamento 20 o 25 anni fa.

Ai giorni nostri, c'è molta “impollinazione incrociata” tra i giochi, per così dire, e c'è molta più attenzione, credo, a interpretare i personaggi come esseri umani più approfonditi, o esseri nani, o esseri elfi o qualunque cosa siano. A interpretare personaggi con personalità un po’ spinose o ammirevoli, che hanno legami reciproci e con il mondo che li circonda, ecco cosa conta nel gioco.

E penso che sia molto più diffuso ora nella maggior parte dei giochi, rispetto agli anni precedenti. Siamo tutti ispirati l'uno dall'altro e prendiamo in prestito l'uno dall'altro. E penso che sia una cosa grandiosa, perché migliora l'esperienza di ogni gioco, ed è una cosa che apprezzo, perché sono un giocatore.

Quello che stiamo vivendo è un'era molto interessante nella storia del gioco di ruolo, come vedi questo grande rinascimento? Esiste il rischio che il mercato collassi su se stesso, dato l'elevato numero di giochi che vengono costantemente pubblicati?

Penso che il rischio di collasso sia molto basso in questi giorni, perché la maggior parte degli editori di giochi che sono ancora in circolazione e che sono in circolazione da molto tempo e che sono sopravvissuti, come Arc Dream e molti altri, hanno imparato a fatica, quanto sia tanto importante concentrarsi fortemente sull'interazione diretta con i propri clienti e sulla vendita diretta a loro, quanto raggiungere i negozi e i distributori e vendere a loro.

Si deve fare entrambe le cose, se non si interagisce direttamente con i clienti, non si crea un proprio pubblico, che alimenterà le vendite al dettaglio.

I tempi in cui abbiamo visto l'ultimo grande crollo del mercato risalgono a circa 15 anni fa, quando c’è stato il grande boom del D20, dopo la terza edizione di Dungeons & Dragons e dopo il rilascio della Open Game License, che ha dato il permesso a chiunque di pubblicare materiale per Dungeons & Dragons. E ogni editore sotto il sole ha iniziato a creare cose per D&D, poiché sapeva che D&D era il grande motore del mercato.

Ma a quel tempo, nessuno stava facendo crowdfunding, alcuni stavano mettendo in atto programmi di preordine, che servivano allo stesso scopo del crowdfunding, ma non per i prodotti D20, perché gran parte dell'editoria D20 era composta solamente da piccole avventure. Quindi, tutti si affidavano ai negozi e alla distribuzione al dettaglio per la parte principale delle loro entrate; di conseguenza, quando si è verificato il crash del mercato, non è stato causato dal pubblico tanto quanto dalle modalità di vendita.

Ogni negozio ha uno spazio limitato sugli scaffali e se riceve trenta moduli per D&D D20 da trenta diversi editori, ne venderà solo la metà e poi dovrà vendere il resto scontato, solo per sbarazzarsene, o restituirlo al distributore, se ha un accordo di restituzione.

Quindi, mantenere quell'enorme afflusso di materiale nel commercio al dettaglio è stata una sfida enorme ed era qualcosa che i rivenditori non potevano sostenere, perché la distribuzione al dettaglio di questo hobby, specialmente negli Stati Uniti ma penso che sia così in tutto il mondo, è su piccola scala, e quindi c'è un limite a quanto sia possibile aumentare sia la portata di un singolo editore sia la portata del settore stesso, nella vendita al dettaglio.

Eravamo diversi editori, e noi siamo stati tra quelli che ne uscimmo bene; c'erano moltissimi editori su piccola scala, molti di loro erano nati esplicitamente per approfittare della Open Game License e si unirono al boom del D20. E poiché non esisteva ancora alcuna stampa on demand, tutti dovevano avere un magazzino, ancora prima di spedire alla distribuzione.

E ci furono un paio di aziende che entrarono nel mercato come consolidatori, come fulfillment house, come le chiamiamo noi, per soddisfare tale esigenza. E quindi ciò che le case editrici facevano, era assumere una società come la Wizard’s Attic, che aveva grandi magazzini e immagazzinava prodotti per un centinaio di piccoli editori diversi.

E poi lavoravano per gli editori anche come agenti di vendita, contattando i distributori e dicendo: "Ehi, abbiamo tutti questi editori, quali vuoi?". E così avevi questi due o tre consolidatori, ognuno dei quali cercava di vendere a forse una dozzina di distributori in tutto il mondo. E ognuno di questi distributori vendeva a questi piccoli negozietti.

Quindi, una volta che i piccoli negozietti avevano raggiunto il limite di ciò che potevano permettersi di acquistare, questo rappresentava anche il limite di ciò che i distributori avrebbero ordinato e a cascata andava a incidere sui consolidatori, limitandone le capacità. E così, i consolidatori trovarono impossibile sostenere quell'attività, poiché dovevano spendere molto del loro denaro in spedizioni, in deposito e manodopera e non erano in grado di recuperare tutti questi costi attraverso le vendite al dettaglio.

Okay, ho speso un sacco di parole, per dire che in questi giorni tutto funziona in modo molto diverso e la differenza più grande è che le aziende che sono in grado di cavarsela, hanno diversificato i loro flussi di entrate. Vediamo ad esempio Arc Dream, perché non ho motivo di parlare per nessun altro, con Arc Dream vendiamo al dettaglio e abbiamo risultati abbastanza buoni, amiamo vendere ai negozi e facciamo tutto il possibile per supportarli.

Pertanto, un terzo forse delle nostre entrate annue provengono dalle vendite al dettaglio, ma un altro terzo proviene dalle vendite e dai download di PDF e l'altro terzo dalle vendite dirette dei nostri manuali fisici (e PDF perché li diamo gratuitamente insieme ai prodotti fisici) ai singoli giocatori.

Quindi, se il mercato al dettaglio dovesse di nuovo crollare all'improvviso, ciò ci farà del male ma non ci ucciderà, perché possiamo adeguarci a perdere un sesto o un terzo delle nostre entrate, ma nessuno potrebbe adattarsi a perdere il 90 % delle proprie entrate, come accadde vent’anni fa. Quindi il rischio di un enorme collasso penso sia molto basso in questi giorni, perché pochissimi editori fanno affidamento solo su una parte del settore per sostenersi.

Inoltre, ci sono programmi di crowdfunding, come Kickstarter, che fanno ormai parte di questo settore. Siamo stati tra i primi a fare questo tipo di crowdfunding, all'inizio della metà degli anni 2000, e ne abbiamo riconosciuto il potenziale fin dall'inizio. E rispetto a oggi si trattava di campagne piuttosto modeste.

Ma se vuoi pubblicare un gioco, puoi in qualche modo caricare anticipatamente le entrate, che andranno a pagare i tuoi costi immediati, come ad esempio gli artisti, in modo che non si sentano come se fossero stati derubati, e gli sforzi per mettere insieme il gioco. Inoltre, se il prodotto è caratterizzato da qualcosa di abbastanza elaborato da richiedere un grosso ordine di produzione, è possibile caricare in anticipo tale costo in un programma di raccolta fondi. E il crowdfunding, se lo fai bene, è in grado di prepararti, isolandoti dal mercato, così da subire un’eventuale recessione un anno dopo, poiché hai già coperto molti dei costi.

Quindi, questa è una lunga, lunga risposta per dire che non penso che ci siano molte possibilità che ciò capiti. Penso che sia molto improbabile, perché quasi tutti noi non abbiamo più a che fare con un'entità o con una mezza dozzina di entità (ad esempio i distributori), che potrebbero incorrere in guai che quindi diventerebbero nostri guai. Lavoriamo tutti direttamente con i singoli consumatori. Se metà dei fan di Delta Green improvvisamente si stancassero di ciò che facciamo e smettessero di ordinare, okay lo noteremo, ma le probabilità che capitasse improvvisamente tutto in una volta sono davvero basse, è più probabile che lo vedremo accadere nel periodo di un anno o due, dandoci il tempo di realizzare la cosa e di riaggiustare il tiro.

Penso che tutto ciò sia ottimo per noi come editori, significa che siamo in grado di fare ciò che ci piace senza preoccuparci che fattori che sfuggono al nostro controllo ci faranno esplodere. Se iniziamo a fare cose che non piacciono a nessuno, allora ci troveremo nei guai, ma dovremmo solo metterci a pedalare.

Grazie ancora Shane per il tuo tempo e la tua cordialità, sono state quasi due ore di vero piacere parlare con te.

Grazie Davide per l'intervista! È stata molto divertente e spero che presto potremo parlare nuovamente.

The interview with Shane Ivey in English

Hi Shane, thank you for your time. We know that you are Co-founder and President of Arc Dream Publishing as well as author of many role-playing games published by Arc Dream Publishing. Tell us something more about yourself: when did you approach the world of role-playing games? What prompted you to become a game designer and start your own publishing house?

Hi Davide, It’s a pleasure. I got into RPGs as a ten-year-old kid with the first version of Basic D&D and it was a hobby for a long long time. I only started getting involved with the publishing side of things when I was, oh I don't know, I was in law school in New York and very bored and started playtesting a lot of material for Pagan Publishing, which is a company that did Call of Cthulhu books that I absolutely loved, and started working with them more and more as a volunteer and just as a fan for several years.

In the meantime I switched careers and I started working as a writer and an editor in other media: in magazines, newspapers, websites, and meanwhile I was still doing some freelance work for role-playing game companies, like Pagan Publishing and a company called Hobgoblin Press, which had started to publish a game called Godlike that my friends at Pagan had put together.

When after a year to working with Hobgoblin in a very light capacity, I got together with Dennis Detwiller, who I knew from Pagan Publishing and who was the one who had suggested that they hire me, and we took a week we made an arrangement with Hobgoblin to publish Godlike for ourselves through a new company. That's how we started Arc Dream Publishing.

That was in maybe 2002 so that was a long time ago now and so after that, you know, I ran well I mean I ran Arc Dream Publishing pretty much full-time since then, but of course I've only been able to get paid full-time for full-time work, you know, a few of those years here and there so, but yeah that's how it happened.

So, we just did, we did a lot of projects for Godlike, for a couple of spin-off games based on Godlike, such as Wild Talents, which was also a very kind of gritty superhero game and Better Angels, and we relaunched The Unspeakable Oath, which was Pagan Publishing's flagship magazine, that I adored.

And eventually, after about 10 years, we worked with Pagan Publishing to start putting out new material for Delta Green, which is my favorite of their properties.

And that's become our focus since then, because Delta green is the work that really strikes a chord the most with gamers of everything we've done, and we've been fortunate enough to make it to build on the success that Pagan had with it all those years, and keep the principle authors from those days involved now at the same time.

We have just published a rather comprehensive review of the two Delta Green Core Books, but we think it would be stupid not to take advantage of the presence of one of its authors, therefore, explain us, what is Delta Green?

Oh yeah, sure, so Delta Green is a horror role-playing game, it's set in the modern day and it has the players take the role of professional investigators, who in other words mostly they may be police officers or FBI agents or what have you, or they might just be doctors or, you know, or history professors or whatever. But they are involved with an organization that is aware of terrible, unnatural, terrifying dangers in the world and strives to protect the world from them.

And part of that, in the organization's mind, is keeping them secret and hidden, so that they harm the fewest people. And so in the game, you're the players, then to their characters are told there's this dangerous incursion at this place, in this tow: “so go there and find out what's happening and stop it from hurting anyone else. And above all, keep it secret and keep us secret as well and try not to get killed or go insane in the process”.

So, I think the reason that it works as well as it does, is because it's not as straightforward as “just go in and fight the monster”, right, you have all these layers of secrecy and danger that affect each other like a web. And so, the players constantly have some source of tension and suspense and danger affecting their characters, no matter what they do or how successfully they do it.

So, it's meant to be very tense and very suspenseful and very thrilling and, at the same time, it's meant to really draw out that sense of kind of cosmic terror that makes your head spin if you think about it in the right way, that we enjoy so much.

In my review I wrote that if Lovecraft and Tom Clancy had ever written a four-handed novel, the result would have been something very similar to a Delta Green novel. Do you think it is wrong or is there something true in this statement?

Yeah, that's pretty good, that's pretty good. We've all done so much reading in kind of modern thriller fiction and in history of course as well, you know. I think of it I think a bit closer probably to John le Carré than Tom Clancy, because le Carré emphasized tradecraft and secrecy and the dangers of kind of bureaucratic backbiting and the danger and the inherent sort of inhumanity of keeping deadly secrets from people, without thinking of anything except the need to keep secrets.

So, I personally think that le Carré is a better match than Tom Clancy, but if you're trying to get the point across to the most people, who don't know the difference between John le Carré and Tom Clancy, sure, yeah.

In recent years, we have witnessed a real explosion of products related to the Lovecraft’s Mythos, including role-playing games, boardgames, gamebooks, merchandise and so on ... What do you think is the reason for such success?

Oh yeah, well I don't even see it as a recent thing necessarily, I mean certainly in the past few years because Chaosium came back around in such a big way and put out a new edition of Call of Cthulhu and has been putting out a steady steady line of really good books for Call of Cthulhu, that's gotten a lot of attention.

But for ten years before that there were maybe half a dozen other licensed companies putting out fantastic books along the way: Cubical Seven and you know of course we did, and Pagan and Golden Goblin Press, Miskatonic University suppressed.

So, it's been successful for years and years and years, I mean going back to the very beginning, it's never gone away. The reason for that, I think is because… Well you know, I think there are a lot of gamers who once they get into role-playing games, they have a great time playing the games - most people come into role-playing games through adventure games like Dungeons and Dragons primarily - and they have a fantastic time, but then they learn there are other genres available that feel different, right?

And just as there are plenty of people who would rather see a horror movie, a surreal horror movie like White House or Annihilation, than The Fast and the Furious, there are plenty of gamers who once they play a horror game and find to the suspense in that and the danger to your characters and the different ways that you have to play a character, they really respond to it and that becomes something that they'll just dig into and keep coming back to.

Personally, I'm always interested in the capacity for role-playing games to explore different genres, because it's primarily still overwhelmingly an action-adventure medium, right? You play heroes with swords or spells that blow monsters up and you go around and you fight, fight, fight and then you get gold and magic items that make you better at fighting and fighting, right?

And that's great, it's fun, but it's always interesting to me that there is such a large world of storytelling out there and there are so many ways of evoking tension and suspense in narratives, beyond just violence and fight scenes, that even to this day we've barely scratched the surface of that in role-playing games.

But I think, coming back to your question, the reason that people respond to horror games is, I think, exactly that once they realize that they can still play a game where they get in the head of the character and sort of vicariously have these amazing experiences, but it's a character who's afraid all the time, you know, you get that same kind of thrill, that adrenaline rush, and it's so much more pronounced because you're playing a character who's vulnerable in ways that the heroes are not.

And I think that's never gone anywhere and I think that's why people keep returning to games like Cthulhu and Delta Green over and over again.

Delta Green was born as a spin-off setting of Pagan Publishing for the 5th edition of Call of Cthulhu and had a discontinuous publication until 2010. What prompted Arc Dream Publishing to focus again on this IP?

Yeah so, Pagan Publishing originally published Delta Green in the magazine The Unspeakable Oath and in a 1997 big Call of Cthulhu sourcebook called Delta Green.

I became a huge lifelong Delta green fan from that Unspeakable Oath article and then spent four years, you know, desperately waiting for the big real book to come out… And it was brilliant. So, but anyway they published that, they published another larger book called Countdown and then they published a handful of shorter books that they didn't sell to stores, so that they didn't have to run afoul of their licensing limitations with Call of Cthulhu.

But then about that time, John Tynes, now John Scott Tynes, who was the principal at Pagan Publishing, he organized everything and ran everything, he moved on to the world of video games instead and so Pagan Publishing's production dropped off sharply after that, about 2000, 2001.

Like I said, I had start about a year or two later, and Dennis and I started working together closely and so, from the very beginning, he and I talked privately about ways we could jumpstart Delta Green again and get back to writing Delta Green.

I had a lot of ideas for it, he was one of the creators and was filled with ideas for it, that he wanted to see take shape. And it just took a few years for us to establish ourselves well enough as a company and to work things out with Pagan Publishing which is run by Scott Glancy now, who's one of the other creators of Delta Green, to sort it out.

And at first we, at Arc Dream, we published two Delta Green books, one called Eyes Only and one called Targets of Opportunity. Well, actually Pagan Publishing published them officially, Arc Dream created them and sold them. You know, created them as a studio, we published, packaged them and publish them with Pagan Publishing slow go on and in conjunction with Scott Glancy at Pagan Publishing.

And then, they published it under their license with Chaosium. So what we had was essentially a break-in Delta Green from the time Countdown came out in 2000 until say 2007 when Eyes Only came out. And all through that time, we were talking about how do we get back to it and it was about 2004 that we started really working hard on putting Eyes Only together, and it just took a couple of years to make that happen.

So, that was always part of our goal figuring out some way to keep Delta Green going, because Dennis and I, I mean on top of just loving the property and loving to work on it, we knew that the audience was still there, because we interacted with the fans every single day, on mailing lists and websites. And they remained just as active when we went years without putting things out as they were active when there were books coming out frequently.

So, it was once we got everything arranged, we put out Targets of Opportunity in 2010 and it did well, and so we immediately turned our eyes to how do we launch this game as its own game. And we didn't have in mind exactly rebooting the property, because from the very beginning, we explicitly wanted anyone, who had bought anything for Delta green before, to be able to use those books and those rules with whatever we came out with next.

We didn't want to make anything obsolete, but so we spent a long time over the course of several years figuring that out, working and talking between ourselves. We brought in colleagues of ours who were extraordinarily well versed in the Cthulhu Mythos, both as a mythology and also as an intellectual property, and so that we could sort of set the boundaries of what can we do with this property that won't run afoul of our friends at Chaosium.

Because we didn't want to step on their toes but we also didn't want to be limited by a license that required us to get permission from someone else every time we wanted to produce something. And along the way, our friends at Pelgrane Press created Trail of Cthulhu, which took its own different approaches, and so there was a lot going on in the field that sparked our interest and it generated ideas.

So, after we put out Targets then it took just a few years of figuring all that out and deciding what we wanted a new ruleset to look like and feel like. And that took a great deal of work before we felt we could officially say: “here's what we're doing” and then bring it to the fans, you know, to raise money for it.

What were the biggest challenges you faced in developing Delta Green?

Oh, well, I think the biggest challenge always is getting the mood and the tone right, because with Delta Green our approach it's distinct from the way most Cthulhu books are written, it's distinct from the way most Cthulhu Mythos adventures are presented. Dennis and I, particularly, and John Tynes and Scott Glancy, we all have kind of an instinctive intuitive sense of how that should feel it and in play, but articulating that it is much harder.

And even delivering it, delivering books and adventures that have that sensibility to them, is always kind of a challenge, because even as an author for one of us it's very easy to sort of get focused in the details of the world, the historical details, procedural details of how these secret conspiracies and organizations work, and then lose focus on the what tone and mood all the supernatural stuff should evoke.

So, that I think that's the one biggest challenge all the time, especially because, you know, as like I say even those of us who are authors who have the deepest experience with this, still stumble over it and we still have to work with each other to make sure you know everything.

Every time I write something for Delta Green, I send it to the rest of the Delta green partnership party:

Dennis Detwiller, Scott Glancy, John Scott Tynes, so they can read through it and review it and point out: “okay, this doesn't feel right, this doesn't feel right, this part here is great…”, you know, and we all do that with each other. So, every time Dennis does write something I go through it with a fine-tooth comb and just poke at it, you know, and send him millions of annoying notes.

But that's part of the process and that's how we make sure that everything we do is good as none of us get our egos involved. None of us get precious about what we do, because we are all here to kind of serve the property because that's something that we share together the value in it. So yeah, that's the biggest challenge I think, is making sure that every Delta green thing, no matter what the subject is, it has that very stark bleak sensibility about it.

Because we know that players are going to come to the table, and they're going to bring their own sense of humor, they're going to bring their own sort of kind of black comedy and tasteless jokes and ways to kind of cope with the very hard cosmic, almost nihilistic, sense of the world that we're giving them.

So, we deliberately want to keep it almost as dark as possible so to speak. Yeah, that's the big thing, there are plenty of other challenges, but that's the big one.

The Delta Green rules are maintaining the Basic RPG system by Chaosium as the base of the game engine, but they introduce many new features and a game design that I really appreciated, from the lethality rating to the management of mental sanity. A mechanism that I would call fundamental is the Bonds and how the contact with the unnatural is going to erode the lives of the characters, together with the intake of alcohol and drugs to be able to carry on, despite what has been witnessed. All this makes Delta Green a very adult, grim and murky product. Tell us something about it, how did you arrive to these fantastic rules?

Yeah, sure, thank you! I think every it's interesting because every one of those things, of those elements of the rules, came about independently from all the others and at different times and in some cases, by different authors. The lethality rules, for example, were developed by Greg Stolze, who we worked with on Delta green the roleplaying game.

He was the rules developer for Godlike and Wild Talents, Better angels, all these fantastic games, and Unknown Armies, that that we just love, and so we love working with him. But that was funny, because I remember that he's talked about the one experience that inspired him to come up with something like that.

Was a game that I played in with him at Gen Con one year, that Scott Glancy was running; it wasn't a Delta Green game, it was a World War One game and we were playing sailors on a submarine. And the submarine encountered some horrible, evil, monstrous cult somewhere and at one point one of the players went, you know, insane and was on a machine gun on the submarine and said: “I'm gonna start killing everyone” and so he said: “Okay, let's roll your attacks with the machine gun”.

And at that moment, the whole game ground to a halt, because that player started rolling: “Okay, here's a roll to hit, here's a roll to hit, here's a roll to hit, here's how many bullets this guy takes, here I'm in a roll damage for every one of these bullets…”.

And Greg has said that was the experience, that was his moment if there has to be a better way and so he started, he kind of played with the idea here and there for a couple of years and then when we were pulling the Delta Green role-playing game together, he sent it over and it was probably about 85-90 % already done and ready to be published at that point.

So, we did a lot of play testing with it and kind of streamlined a couple of the rules elements here and there, and then it was ready to go, it was kind of a stroke of brilliance on his part, but he saw something where there was a challenge, and where adding a new rule could enhance both the fun of play and the suspense and the sense of fear in the players at the same time.

It was brilliant genius, I love the way that those rules work when they come in into play. The other things, the tweaks that we made to the sanity rules and to bonds, were mostly my work. I approached those elements basically because there were parts of the existing sanity rules that I really, really, loved, obviously or I wouldn't have been playing these games for, you know, 20 or 30 years or whatever it was at that point, but also we knew we were setting this in the modern day.

And we were setting this game in among players in the real world, many of whom had recent experiences of war and of trauma and of the traumas that we were kind of replicating in the game and turning into something to do for fun. And so, I very much wanted to make sure that the course of experiences of a Delta Green agent in the fiction would look familiar to someone who knew, who had direct experience of what that course was like dealing with terrible traumas in the real world

And one of the key parts of that is the impact that PTSD and that other trauma symptoms and syndromes have, not just on the individual who suffers from them, the patient, but on everyone around them, all of their family, all of their friends, and that it's always never really been a feature of horror games, in my experience. It's something that you were kind of encouraged to you know as the player: “Okay, now you fill in all those details and make it up as you go”.

So, I thought it would be much more interesting and powerful to have some parts of that be built into the rules, that we presented them. And once I started doing that, I had already done a lot of reading in psychology and trauma and I conducted interviews with psychologists who work with the Veteran Affairs Bureau, here in the United States, who work with soldiers, our veterans, to cope with addiction and cope with PTSD.

So that we could kind of the experience of what happens in play like, I say would look familiar and also would approach it with enough seriousness that it was clear we weren't just trying to make a joke out of it and so that was a big challenge. It was a really satisfying process for me, because that's a kind of small set of rules that I had, without realizing it, spent 20 years kind of preparing myself to write, but that I knew instinctively were gonna play a powerful role in the new game and do a lot to set it apart from everything else that we did that had come before.

So, that's how that came up and there are other tweaks to the rule engine, but most of the other ones are fairly minor and they get into some very detailed things. You know, it's a percentile engine and you roll percentile dice and if it's low enough, then you succeed, but then there's a chance that you might succeed really, really, well, which in some games that's you roll a certain fraction of what you need so if you have a 50% chance, if you're all half of that then you do better, if you roll a fifth of that then you do better and you can do all this math…

So, I was talking to Greg Stolze and we borrowed ideas that he had built into Unknown Armies, and that we had seen in other games elsewhere, like Pendragon and Eclipse Phase, to come up with an alternative to that, that would be much easier and more intuitive.

So, instead of having that system be based on fractions, it's just you roll the dice and it still if you roll low enough you succeed, but you look for matching numbers instead and therefore the better you are the skill the more likely you are to get that magic number. And that solved like all of those problems immediately.

That's a very detailed thing, but there we kind of did that with a lot of parts of the rules engine to kind of streamline it and make it easy to play.

I also particularly appreciated the choice to give the game a more scientific and less "magical" point of view of the Cthulhu Myths. We are dealing with hypergeometry and hypermathematics more than with magical and esoteric forces. Even the choice of the word "unnatural" instead of the more common "supernatural" is a clear sign of this stylistic choice, which I believe is more in line with Lovecraft's poetics. What made you decide to do so? Do you think that this moving away from the “comfort-zone” of magic they have been used to for years have stunned some players?

Oh yeah, I think it worked fine for players, I don't think I've heard any players who read it who didn't like that approach. And as you say, that was a very careful deliberate choice that we made and that we wanted to reinforce throughout the rules and throughout the Handler’s Guide especially. Because, number one we wrote all of these things from the idea that you're reading this as a Delta Green agent and so all of the information you have is coming through the filter of this secret conspiracy.

And the secret organization, applies all of these precise scientific labels to things that it doesn't understand, because it doesn't understand them and so giving things a very scientific sound, a very scientific label, gives you the illusion of having some sense of understanding or control over it. A control that you don't actually have.

And so, we use the terminology to evoke that and also at the same time to kind of subtly or subliminally keep reminding the players that their characters and the people that they trust don't really know what they're doing and therefore the ground underneath you is unsteady.

And at the same time, what you said, it felt like it fit with the way that Lovecraft just writing. As we've said many, many, times to remind people we're reading today H.P. Lovecraft's stories that were written in the 1920s the 1930s and they often are very quaint and very archaic, but that's not how he was intending them. He was writing cutting-edge science, he was writing all of his best stories based on the most advanced scientific understanding of the day that he could wrap his head around.

So, the story The Call of Cthulhu, for instance. You know that a lot of the impetus from that came because he was learning about radio and about how radio waves work, and obviously found it fascinating and found it kind of weird. And so that informed that sense of these invisible waves and patterns of energy that we have no idea are out there, but that when we kind of tune a couple of gadgets together, then it makes them magically start deciphering those patterns into something that we can understand.